ENTANGLEMENTS

ENTANGLEMENTS

BY: SUMITA S. CHAKRAVARTY

“The Multiplication of Perspectives” was the title of a conference hosted by the Museum of Modern Art in New York recently (April 26-28, 2019) to mark the 10th anniversary of its Global Research Initiative, C-MAP. The event brought together scholars, artists, and curators to present their work on a variety of topics relevant to a variety of contexts that had the overarching aim of defining the relationship between local and global, the particular and the planetary. With such an expansive scope, it is not surprising that the views put forward and the questions posed touched on some of the most intractable issues of our time, from climate change to terrorist attacks, from neoliberal policies of extraction to the cybernetics of colonialism, from the philosophy of reason to the advent of the post-machinic world. The topic of borders and forced migration constituted a steady drumbeat throughout the talks, perhaps the surest means of actualizing the notion of the global that the panels struggled with, and struggled against.

“The Multiplication of Perspectives” was the title of a conference hosted by the Museum of Modern Art in New York recently (April 26-28, 2019) to mark the 10th anniversary of its Global Research Initiative, C-MAP. The event brought together scholars, artists, and curators to present their work on a variety of topics relevant to a variety of contexts that had the overarching aim of defining the relationship between local and global, the particular and the planetary. With such an expansive scope, it is not surprising that the views put forward and the questions posed touched on some of the most intractable issues of our time, from climate change to terrorist attacks, from neoliberal policies of extraction to the cybernetics of colonialism, from the philosophy of reason to the advent of the post-machinic world. The topic of borders and forced migration constituted a steady drumbeat throughout the talks, perhaps the surest means of actualizing the notion of the global that the panels struggled with, and struggled against.

How does one build a multiplication of perspectives? The conference did so through an organizational as well as dialogic approach: C-MAP Fellows, the planners of this event, represent different regions of the world: Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Central and Eastern Europe. This somewhat traditional “area studies” configuration serves as a palimpsest for the central tension of the global, more on which below. However, rather than organize the panels as region-specific, the organizers instead foregrounded more “unifying” (or “entanglement”) themes such as borders, returns, circulation, crossings, and incommensurability. Dialogue, forum, screening, and keynote also created rubrics of exchange that would accommodate diverse viewpoints and positionalities. The result was a stimulating, if poignant reminder of our current human situation in which increased global cultural traffic has not necessarily resulted in increased understanding of otherness or, arguably, of the self.

Indeed, the idea of translation and of untranslatability –of languages, traditions, objects, meanings–emerged as one of the key signifiers of our contemporary cultural moment. Does an obelisk physically transported from Rome to Ethiopia in an act of restitution of cultural property appropriated during the colonial period mean the replacement (as if that were possible) of an uninhabited past? Where does the obelisk belong, the place where it marks a chapter in the ongoing history of colonialism, or the place which was victimized and marginalized, and is now seeking reparation? What does it mean to treat an African fetish or communal religious icon as an art object? Does death look the same in different cultures? How we translate is inevitably imbued with the circumstances that have shaped our thinking, and the context from which we speak or listen.

Two themes particularly stood out to me as key ideas being debated at this conference: the relationship of local/regional, global, and planetary; and the question of borders — what they mean, how they affect lives, and what we can do about them. In the first, the new entrant in critical analysis would seem to be the planetary, a concept that subsumes both local and global as new technologies have now made it possible for scientists to take the earth itself in their purview, and as climate change makes it imperative to do so. Both local/global intertwinings and the politics of borders were informed by histories of colonialism, and various speakers deftly traced the macro and micro processes of this still-unfolding scenario. To briefly recap the local/global debate, a strong strain of critique has pointed to the ways in which the forces of global capital have tended to eradicate local economies and cultures, thereby extending inequalities of wealth and power between north and south. In terms of art, long-established hierarchies of center and periphery are slow to be dismantled, leading many to return to the specificity of the local and the need to support local identities and practices.

These debates are by now quite familiar in scholarly circles. But what was truly fascinating was the contrasting perspectives on the planetary by the two keynote speakers. Dipesh Chakrabarty drew on the work of earth scientists and geologists to tell us about the incommensurability of human time and geological time. In a highly complex argument that cannot be summarized here, he drew the conclusion that, unlike in the era of globalization in which the rich get richer and the poor poorer, in the face of climate change, everyone’s survival is at stake. Achille Mbembe’s closing keynote brought us firmly back to the here and now, as he laid out four mega-processes in the contemporary world : (1) unprecedented concentration of power in the hands of private corporate entities; (2) technological escalation in which all societies are organized as computational, as systems to process data; (3) the trading of “life futures,” as more and more of life becomes quantifiable; and (4) the erosion of Reason, or the replacement of human reason by machines. His somewhat apocalyptic vision of the planetary, or what he termed “the post-machinic world” concluded with a plea for human freedom as a space for the incalculable, the incomputable.

Both the global and the planetary as theoretical perspectives entail border-crossing of one kind or another, so it is no surprise that the conference in general was heavily invested in rethinking borders as actual and metaphoric entities. Two ideas were particularly intriguing. Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz of Bolivia spoke of the “institution of the skin as a double difference,” whereby our sense of self is bounded by the skin. But, he suggested, we are constantly exceeding the skin; the body is a process in constant flux, with infinite molecular movements. Closing off inside and outside processes of movement kills off the individual. “Two-thirds part of me is outside of me,” he suggested. Another speaker problematized the idea of co-relation by suggesting that contact creates boundaries even as it removes boundaries. The challenge then is to come upon a space of correlation as a space of co-creation. The complicated issue of boundaries was brought to a close with a screening of Jumana Manna’s powerful film of Israeli-Palestinian musical correlations, A Magical Substance Flows into Me.

All in all, the conference left us with as many questions as there were answers, which a good conference is supposed to do.

THE CRIMINAL IMMIGRANT: MYTH, ENEMY, ICON (PART 1 of 4)

BY: JEN EVANS

“[Mexican illegal immigrants] are bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” — President Donald Trump, 2015

“[Mexican illegal immigrants] are bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” — President Donald Trump, 2015

“[Mexico] has been overtaken by lawbreakers from the bottom to the top. And now, what you’re protesting for is to have lawbreakers come here.” — Political Commentator Glenn Beck, 2006

“The character of immigration has changed and the newcomers are imbued with lawless, restless sentiments of anarchy and collectivism.” — Rep. Albert Johnson, 1924

“Any alien, being a free white person, may be admitted to become a citizen of the United States, or any of them, on the following conditions … he has behaved as a man of a good moral character, attached to the principles of the constitution of the United States, and well disposed to the good order and happiness of the same.” — Naturalization Act, 1790

The notion of ‘the criminal immigrant’ is pervasive in current political rhetoric. Images of foreign-born street gangs and criminal organizations are harnessed by proponents of immigration reform, stricter border security, and stronger response to undocumented migrants. Meanwhile, opponents of such rigid migration policy argue against the categorization of immigrants—even undocumented immigrants—as criminals, often citing racial persecution and the misrepresentation of data as contributing to depictions of immigrants as unlawful or immoral.

Amid such chaotic debates across both media and political landscapes, it can be easy to forget that the ‘criminalization’ of immigrants is a long-established phenomenon. Societal fears of differing cultures and moralities date back to the earliest days of immigration. In the United States, such concerns were expressed as early as the Naturalization Act of 1790, when the obtainment of citizenship was reserved for ‘white men’ of ‘good moral character.’ Those of us who have completed American immigration proceedings more recently may attest to lasting queries regarding our so-called moral character, including questions pertaining to potential involvement in everything from drinking and gambling to genocide, communism, and the recruitment of child soldiers.

Amid such chaotic debates across both media and political landscapes, it can be easy to forget that the ‘criminalization’ of immigrants is a long-established phenomenon. Societal fears of differing cultures and moralities date back to the earliest days of immigration. In the United States, such concerns were expressed as early as the Naturalization Act of 1790, when the obtainment of citizenship was reserved for ‘white men’ of ‘good moral character.’ Those of us who have completed American immigration proceedings more recently may attest to lasting queries regarding our so-called moral character, including questions pertaining to potential involvement in everything from drinking and gambling to genocide, communism, and the recruitment of child soldiers.

Indeed, America’s history is rife with concern regarding the ‘moral character’ of migrants. Such anxieties are often opposed on the grounds of racial prejudice, noting examples such as President Donald Trump (2015) and Rep. Albert Johnson (1924) as having targeted specific ethnic groups with accusations of “unlawful” or “immoral” behaviors. Yet despite debatable data and questionable motives regarding the criminalization of immigrants, one fact remains certain:

A small number of immigrants are criminals, and those immigrants have played an important role in the joint histories of media and migration.

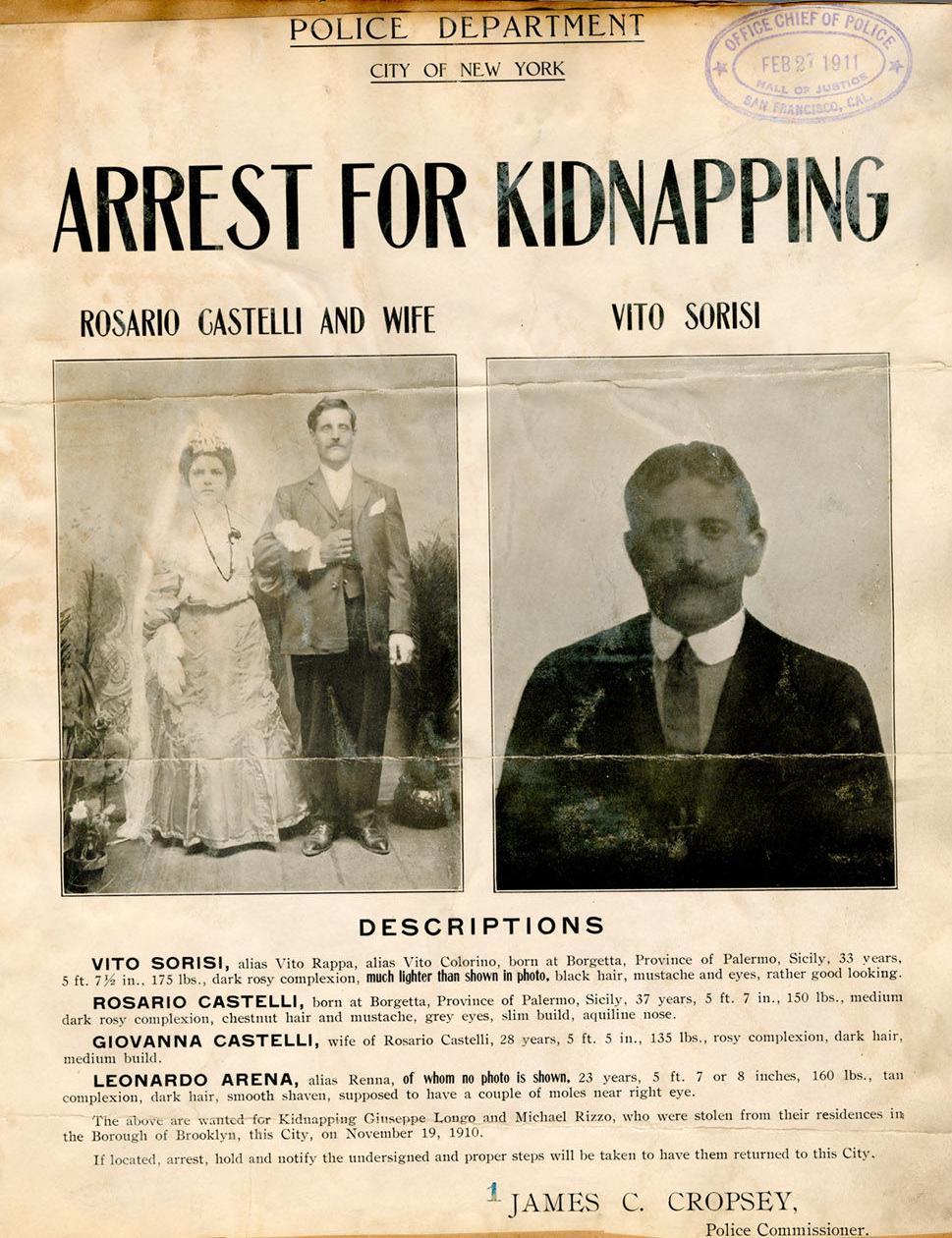

Among the most prominent examples of criminal immigrants are the founders of the historic Italian-American Mafia. Members of the Sicilian Mafia first immigrated to the United States circa 1881, but it was not until 1890 that America’s first major Mafia incident occurred. The execution-style murder of the New Orleans Police Superintendent resulted in public outrage, and hundreds of Sicilians were arrested as part of a manhunt to locate the parties responsible.

More well-known iterations of the Italian-American Mafia were established in the early 1900s. Organized criminal syndicates emerged in areas such as New York and Chicago, led by iconic mobsters—and immigrants—such as Lucky Luciano and Carlo Gambino, as well as children of immigrants, such as Al Capone.

America’s new criminal syndicates quickly became known and feared for practices including kidnapping, extortion, and murder; and media producers hastily capitalized on the nation’s growing panic surrounding the Mafia.

The first ‘Mafia film’, The Black Hand, was released in 1906, with D.W. Griffith’s The Musketeers of Pig Alley following in 1912. Both films depict criminal characters, and their respective organized syndicates, as distinctly villainous, victimizing the more prominently featured protagonists.

It may seem an obvious choice to cast the violent and criminal Mafia as antagonist; however, the ‘evil Mafioso’ starkly contrasts modern portrayals of the organized Italian-American criminal. Considering the anti-heroes of The Godfather, Scarface, and The Sopranos, one is confronted with the question:

How did ‘the criminal immigrant’ itself migrate from enemy to icon in American culture?

The “mafia movie” and, now, television genre has emerged as a powerful lens with which to approach the history of cities and towns (New York, Chicago, Jersey City), to take the measure of charismatic anti-heroes, and to comment on the American experiment itself. It might be advanced that the criminal mind is particularly in focus in popular media shows at the present time. Thus, an exploration of our ongoing fascination with the cultural other can yield valuable insights into the nature of social reality itself.