THE CRIMINAL IMMIGRANT: MYTH, ENEMY, ICON (PART 3 of 4)

BY: JEN EVANS

“Nowadays, crime’s gone respectable.”

These were the words of Captain James Hamilton, Head of Intelligence for the Los Angeles Police Department, as he described the Italian-American Mafia to Ian Fleming circa 1959.1 In his travels to Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, and New York City, famed crime writer Fleming sought to experience the dark yet romantic underbellies of America’s greatest Mafia towns. What Fleming found in his adventures was a matured Italian-American Mafia, much different from the kidnappers and bootleggers described in Part 1 and Part 2 of this series.

Sources including Chicago Sun-Times crime reporter Ray Brennan, The Nation journalists Fred Cook and Gene Gleason, and a Mafia “front man” describe national syndicates which had graduated from gun battles to the (ostensibly legal) corruption and extortion of businesses, labor unions, and politics. So-called “gangster money” controlled hotels and casinos in key cities such as Miami and Las Vegas. Mafia bosses were well-dressed, lived in exclusive neighborhoods, and offered press interviews. Entire municipalities were operated by Mafiosos, with one New York City election failing to offer a single candidate without Mafia ties.2

Indeed, the Italian-American Mafia had come of age. But organized crime was not the only industry that was changing. Desperate to attract audiences amid the collapsing economy, cinema of the 1920s and early 1930s saw increased sexual and violent content, from gory gangsters films to racy Mae West comedies.3 Notable during this period was 1932’s Scarface, an intense affair based on Al Capone’s rise to power in the Italian-American Mafia.

Scarface highlights a unique crossroads in America’s film history. Amid the rising violence and sexuality in cinema, individual states and municipalities implemented regional censorship boards aimed at enforcing local sensibilities.4 As a way to combat regionally inconsistent censorship requirements, major film producers including Irving G. Thalberg of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), E.H. Allan of Paramount, and Sol Wurtzel of Fox agreed to broad self-censorship, first (1927) via a self-prescribed list of regulations and later (1930) via the more formal Motion Picture Production Code.

At the time of Scarface‘s production in 1932, the Motion Picture Production Code was ineffectively implemented and enforced, allowing such violent and sexually suggestive films to be presented to audiences despite concerns of government officials, religious leaders, and members of the public. Gang-related films, in particular, were charged with presenting ambitious and hard-working anti-heroes to audiences; allegedly making crime appealing to those similarly hard-done-by viewers of the Great Depression.5

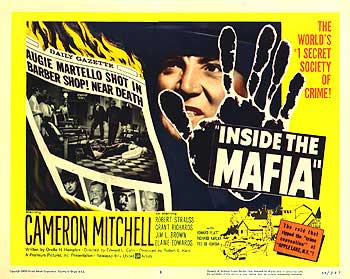

1934 saw the creation of the Production Code Administration, which established authority and an official process for enforcing the Motion Picture Production Code. This enforcement of “the Code” led to a decrease in portrayals of the Mafioso anti-hero, with filmmakers instead required to depict Mafia characters and activities as definitively negative.6 The result was a decline in the production of Mafia films overall, with the genre becoming nearly obsolete from the 1934 creation of the Production Code Administration until the abandonment of the Code in the late 1960s. A slim few Mafia films were produced in America during this time period—perhaps most notably 1959’s Inside The Mafia—a mere shell of the genre which dominated in decades prior.

This era is seemingly a low point for Mafia film. A lull in the genre’s rich history. A period of nothing. But legendary acting teacher Sanford Meisner taught us an important lesson about ‘nothing’: “There’s no such thing as nothing … Silence is an absence of words, but never an absence of meaning.”7 And so, we as media and migration scholars are challenged to resist discounting this quiet moment in Mafia film history, and instead question its meaning.

Perhaps the lack of Mafia films during this era simply indicates barriers to producing Code-appropriate media, or signifies a lack of audience interest in the vilified Mafioso. But maybe it suggests an unwillingness, or even inability, to construct truthful narratives which adhere to censorship standards; which condemn the ‘criminal immigrant.’

This is a particularly important notion within our current media and political landscapes. Media bias—in many ways, a form of strategic censorship which promotes political and social rhetoric on both sides of the political spectrum—is well documented in contemporary American society. Such biases have been especially visible in discussions surrounding migration (see our February 2019 newsletter for details), with media coverage of illegal migration and criminal migrants playing a critical role in recent and upcoming elections.

So what can the ‘righteous’ censorship of Mafia films circa 1934-1968 teach us about the ideological bias of modern migration-related media?

The Motion Picture Production Code and the Production Code Administration did not result in ideologically preferable depictions of the Italian-American Mafioso. Rather, such censorship caused a deficiency; an absence of immigrant narratives which were, only a few years prior, popular among American audiences. This era of Mafia film, or lack of Mafia film, therefore offers a warning which should be heeded: The manipulation of migration narratives—no matter how earnestly in effort to sway audience morality to the side of supposed righteousness—risks silencing the voices and stories of immigrants.

Some may argue that criminal voices ought to be minimized in our society and, thus, in our media. But to do so would also be to minimize important elements of America’s history. Iconic cities such as New York City, Chicago, and Las Vegas have been drastically shaped by the Italian-American Mafia, who helped establish what are now some of the nation’s most prosperous municipal economies.

Indeed, immigrants—all immigrants—are undeniable elements of America’s still-unfolding history. Most immigrants are devoid of criminal involvement. Some are criminals themselves. And too many are vulnerable to becoming victims of crime. Thus, at the risk of media producers and regulators becoming judges and juries of immigrant populations, we must be cautious in censoring the stories of migrants—lest we, in our self-declared righteousness, silence those we ought to protect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2wewG7pdOr4

FOOTNOTES

- Fleming, Ian. Thrilling Cities. (London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1963; Las Vegas: Thomas & Mercer, 2013), 81-83. Citations refer to the Thomas & Mercer edition.

- Fleming, Ian. Thrilling Cities. (London: Jonathan Cape Ltd., 1963; Las Vegas: Thomas & Mercer, 2013), 81-119. Citations refer to the Thomas & Mercer edition.

- Hark, Ina Rae. American Cinema of the 1930s. (New Brunswich, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 12-13.

- Butters Jr., Gerard R. Banned in Kansas: Motion Picture Censorship, 1915-1966. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2016), 187.

- Baxter, John. The Gangster Film. (London: C. Tingling & Co. Ltd.), 7-9.

- Leitch, Thomas. Crime Films. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 26.

- Meisner, Sanford, and Dennis Longwell. Sanford Meisner on Acting. (New York: Random House Inc., 1987), 29.

WHY WE NEED THE MIGRATION-MEDIA NETWORK

BY: SOFIA SILVEIRA

In this issue of the Migration Mapping newsletter, we decided to take a more personal approach as we wrap up a year and more of involvement with this project. We wanted to reflect on our experiences in building it conceptually as well as organizationally: the challenges as well as the rewards of tackling a daunting issue of our time in ways that have been meaningful to us and contributed to our intellectual formation. As we have done before, this also extends an invitation to those who are interested in exploring the intersections of media and migration to become part of this important work.

The show Black Sails is about pirates and the dream of freeing the island of Nassau from the hands of both the British and Spanish empires. The first two seasons focus on a couple that gave up their lives in Europe to try to see that dream come true.

The contrast between the couple’s lives in England and in the Bahamas of the eighteenth century is the most fascinating part of the show. Demonstrated through sharp cuts of past and present, we can get a glimpse of the thunderous differences between the lives they live and the lives they once had.

Migration deeply affects Captain Flint and Ms. Barlow. It affects how they relate to their environment, how they are seen by other characters and how we see them in the show. If Flint does something cruel to secure his position of power, if or when he sees unspeakable violence, he will most certainly look to the horizon in silence. We, the audience, because of those constant flashbacks and how they are positioned, know he thinks of home. When he or Ms. Barlow shows knowledge that could only have been obtained with a fancy European education, or speak personally of powerful British officers, the characters around them, who grew up in the hardship of the new colonies, look at them with suspicion.

The experience of going from one place to another means facing the myths and silent stories that flow in an encounter with members from the local community. In the eyes of the other, one can easily be defined by where they came from. World politics come into play and a migrant is only as good as the relations between their country and the place they now occupy. This multidimensional conflict that is migration affects everyone involved in it and I believe the only way we can collectively process it is through media.

That is why I joined M2lab (a subsection of the broader Media+Migration Network). To explore the many ways in which a migration story can be told and to learn more about the ways in which media can help people process it. Black Sails is just one example amongst a galaxy of possibilities.

When I first contacted Professor Sumita Chakravarty (founder and curator of the Media+Migration Network), it was January 2018. I had just finished university in Brazil, completing the course with a thesis on representations of loneliness in movies focused on migration. I was inspired by the subject and, at the same time, too obsessed to go on thinking about it.

For a year I had studied immigrant loneliness. Then for a year, I experienced it. Then for what has passed of 2019 I was proposed to by someone who is now my husband, falling deeper in love while swallowing the fact that my loneliness might not be temporary. I’m now not only a student, but an immigrant. M2lab became a place to process my pain, confusion, passion and eventual burnout.

Here is what M2lab is: it is an online laboratory for projects that explore the juxtapositions between media and migration. It is the website m2lab.net and one arm of the Media+Migration Network. The other arm is migrationmapping.org: an online archive that registers different encounters of media and migration throughout the world while also publishing a monthly newsletter with reflections on contemporary subjects.

We would meet biweekly: Jen Evans, the intern for MigrationMapping, I, the intern for M2lab, and Sumita Chakravarty, The School of Media Studies professor who founded these projects. In our time together, every meeting was an opportunity to discuss the projects and learn together about connections we had not seen yet.

If before I was overwhelmed thinking about the possibilities of analyzing media that directly addresses migration, I was in awe when I understood that migration and media can be used to structurally explore each other.

What is media but transits and what is migration but media transferred, interpreted and exchanged between the one that bears the messages (the migrant) and the one that involuntary receives them (everyone else)?

Because of my internship at M2lab, I got to understand more about the inner workings of The New School, reflect and develop plans to promote and expand this project as well as practice my skills in writing and filmmaking, focusing on the subjects I want to unveil in my professional career.

To me, there is still nothing more painful and arousing than the psychosocial consequences of migration. The encounters I had by being a part of the Migration+Media Network proved that there are still many discussions to be had about the intersection that gives this collective its name and I enjoyed it so much I will continue to work to make sure this space continues to exist. Not only for NewSchool students but for anyone who wants to join the conversation.

If you are interested in learning more or becoming a part of the Media+Migration Network, please contact us at migrationmappingproject@gmail.com.